I never cared much about politics, and then Farage rolled out his toxic campaign to take back control, or whatever the hell it was called. Like many a bubble-dwelling liberal elite snowflake I was dismayed. “The man is neither a scholar nor a gentleman” was the going joke down the pub.

Brexit shook me out of complacency.

Madam Prime Minister says we’re all Brexiters now and should stand together to defend the island from the big bad Everywhere – we’re all in the same boat, you understand. I find this notion ludicrous. Just because I admit that the waters around me have grown doesn’t mean that I’ll be going down to the galley and making tea for the dimwits busily hacking at the hull.

Regardless, there’s a wider question of what on earth has happened to the place formerly known as the First World. I’m not the only one who’s noticed, and it’s not an entirely recent phenomenon.

In 2002 my completely apolitical friend flew back to France in a hurry to vote for Jacques Chirac (“He’s a bad president, but I can’t allow my country to embarrass me more than it already has”) after Jean-Marie Le Pen came second in the first round of the presidential election. Fast forward fifteen years, and voilà! We have Trump, Brexit and there’s Le Pen fuckin’ junior running in the 2017 French general election.

What’s happening?

Many have blamed the rise of populism in the West on wealth and income inequality, fiscal policies implemented in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, and economic impacts of globalisation.

I’m sure the reasons are legion, but I don’t believe that the deciding factors in bringing this about have been economic. Here’s a paper written by a couple of researchers at Harvard Kennedy School that (surprise, surprise!) supports my view 😉

Globalisation

Back in the 70s the politically correct term for the Third World was “less developed countries”; at that time this included Brazil, Malaysia, China and India.

By the turn of the century the world’s economic landscape had changed. A lot of what used to be the Third World had industrialised, the end of the Cold War brought the former communist countries into the fold of the capitalist enterprise. It didn’t stop there: Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines are the new Asian Tigers; in the Middle East Iran looks promising.

While emerging markets surged ahead, economic growth in mature developed economies slowed. Ermine has written a comprehensive analysis 😉 of what that has done to the perceived living standards of Torygraph’s readers. Yet there are two reasons I find the claims that Those Left Behind are being driven towards populism by economic disadvantage problematic. First, I wouldn’t exactly call the Torygraph demographic “those left behind”. And second, a slower growth does not an economic contraction maketh.

Although comparatively globalisation made a more significant difference to living standards in poor countries – they started from a lower base – in absolute terms we have all become richer. The UK’s median household inflation-adjusted disposable incomes have increased over the past 40 years, and the overall percentage of people living in relative low income has fallen.

Inequality

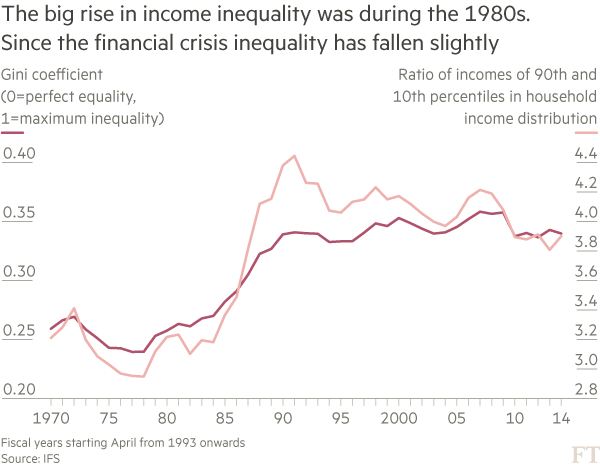

The trend on inequality in the West varies. In the US and Germany it dropped during the 2007-2008 financial crisis, while in France it’s been going up. In the UK, income inequality increased sharply in the 80s, but since the financial crisis it has fallen.

Average net household incomes grew by an average of 2.4 per cent a year between 1961 and 2000. Between the turn of the century and the start of the financial crisis, growth was somewhat slower, at 1.9 per cent a year on average. (Source: FT)

It’s not the economy, stupid

The truth is, neither the US election not the Brexit referendum were won on the economic argument. Experts shmeksperts and all that.

Many areas of Wales that voted in favour of leaving the EU are in fact net recipients of funds from the EU. In 2014 Welsh taxpayers contributed £414 million to the EU but received £658 million in funding; that’s a net benefit to Wales of around £79 per head. Some have called this a textbook definition of self harm. I call this evidence that the motivations which moved the populus to vote with BoJo and Farage had nothing to do with financial interests[1].

So what if Trump’s “amazing infrastructure projects and massive tax cuts, the best tax cuts ever” budget doesn’t stack up. So what if the new president’s priorities having taken office have more to do with allowing oil companies dump sludge in the river and repealing Dodd-Frank than improving the lot of an average white working class Joe. It doesn’t matter. Joe didn’t vote for an economic plan, he voted for bringing back “the old days” when he was THE demographic which held political and economic power.

Inglehart and Norris, who wrote the paper I reference above, argue that the rise of populism has been caused by a cultural backlash rather than an economic shift.

They claim that advancement liberal and cosmopolitan values in Western societies has brought emphasis on issues like environment, gender and racial equality, same-sex marriage, tolerance of social and cultural diversity, secular habits and ethics. While this has increased tolerance of lifestyles, religions and cultures that are different from our own, it has also caused a backlash among less educated and older people, who feel threatened by this change. Those who were once the privileged majority culture resent being told that their traditional values are ‘politically incorrect’ and feel that they are being marginalized within their own countries.

This is significant, because if true, this means that the cultural divide will likely continue to feed populism in the future, irrespective of any improvements in the economic conditions or slowdown in globalisation. Panem et circenses may be their battle cry, but it is not bread they want. Not really.

This also means that there’s a significant difference between what I may think of this shitshow of a situation and what I can do about it. Except perhaps to try and arrange my tax affairs so as to finance it as little as possible. Bring on the end of the tax year, Geronimo.

Notes:

- BoJo was going to stay in the single market, Davis was going to leave the single market, abolish all import tariffs, and wish really really hard that at least some of the chips don’t land in the ocean. There was no coherent economic plan. There still isn’t.

Hmm. The prognosis ain’t good then. We can hope that the old fossils die off in the due course of things, but I fear the less educated will always be with us.

In that case, according to your thesis, we’re doomed 😦

LikeLike

The outlook is not very bright.

What annoys me the most is that the good old Blighty has just made itself poorer in the name of preserving the past. That’s just stupid. We can close the borders, but we can’t stop the tide.

Gone are the times when we could fit out a few ships and go take the Cape from the Dutch, the sun has set on the empire, and I personally think that being a rich medium sized country of medium importance is preferable to being a poor medium sized country of medium importance. But that’s just me, a liberal London snowflake, so what do I know?

LikeLike

yeah, it’s ‘king bananas. reminds me of the old Gore Vidal comment –

“it is not enough to succeed. others must fail”

But I guess I am an older snowflake, I haven’t known repeated fail, but a gradual upswing in the common weal, across the decades, I thought. Until last year…

LikeLike

“And second, a slower growth does not an economic contraction maketh.”

It’s nice to see archaic language used for comic effect, and to reinforce a significant point.

However, the grammar of Indo-European languages (such as English) dictates (grammar really does dictate, I’m afraid) that a clause may only have one finite (declined, inflected) verb, which in this case is “does”. The “maketh” at the end must be the infinitive “make”, no matter whether one is writing in modern or early-modern English.

The arxhaism can be reintroduced by replacing “does” by “doth”, giving: “And second, a slower growth doth not an economic contraction make.”

Hope this helps improve the excellent blog.

LikeLike

You’re right. 🙂 Cheers.

LikeLike